The Old Manse at No. 14 Steeple Street is one of the oldest houses in Kilbarchan. A Latin inscription on a plaque above the main door states that the dwelling house was built in 1730 in the curateship of R I (Robert Johnstoun). Robert Johnstoun was the parish minister from 1701 until 1738.

The manse was a substantial building for the time and continued to house the parish ministers until early in the nineteenth century. It was occupied by the Rev. John Warner from 1739-86, the Rev. Patrick Maxwell 1787-1806, and for some years by Rev. Robert Douglas (parish minister from 1806-1846). The latter two ministers respectively contributed the accounts on Kilbarchan Parish in the Old Statistical Account (1791) and the New Statistical Account (1845). In 1811 a new parish manse was built and the old manse with a small green or bleachfield was sold to a Greenock merchant, James Stewart, in 1817.

Recently, I was fortunate to have access to an old document in the possession of the current owners of the Old Manse. This document contains information on the manse and the adjacent properties with the names of some of the owners dating back to the 1750s. Some of these owners were people who were born or married in Kilbarchan Parish between 1711 and 1740, a period when Kilbarchan Parish Records are missing. From this single document on the Old Manse and a little further research, some interesting information on Kilbarchan’s history has come to light.

The document clearly states that John Warner, Minister of the Gospel at Kilbarchan, possessed the Old Manse ‘with court, offices houses and garden and roads and passages to and from it’. Other owners of adjacent properties in the eighteenth century were John Park, Annabella Sempill, John Barbour, and Agnes Hair, who was the relict (widow) of Humphrey Barbour, and in the nineteenth century the Ramsay family who owned the manse and the surrounding land.

John Park was a Kilbarchan weaver who owned adjacent property. He must have been a prosperous weaver as he was stated as owner of a little yard at the foot and south end of the manse garden and houses which he let to his sub-tenants and cottars, lying within the Vicar Lands of Kilbarchan.

Annabella Sempill, relict of the deceased Ebenezer Campbell, a merchant in Kilbarchan, was stated to have at some time owned a house, a barn and backhouses on the east of the manse. Annabella Sempill’s birth is unrecorded in parish records, but further research revealed that she was born in 1729 and died in 1812. She was the daughter of Robert Sempill, the last Laird of Belltrees, who sold his lands of Thirdpart in 1758 and retired to Kilbarchan. He lived in Belltrees Cottage and is known for his longevity, surviving to the grand old age of 102. He is famed for having witnessed the burning of the last witch in Paisley when he was a child. Annabella married Ebenezer Campbell, the son of an Ayrshire clergyman, and had four daughters, all born between 1751 and 1756. Ebenezer was still resident in Kilbarchan in 1762, but later went to Jamaica where he died.

John Barbour and Humphrey Barbour are mentioned in the document as formerly owning bleachfields adjacent to the manse. Initially it appeared that this John Barbour was John Barbour of Law (d. 1794), the son of Baillie John Barbour (1701- 1770). Both father and son were prosperous linen merchants in Kilbarchan. The document also mentions a house and yard on the east side of the manse garden formerly belonged to the deceased Humphrey Barbour, Merchant in Kilbarchan, and thereafter by Agnes Hair his relict (widow).

However, this presented a bit of an enigma. John of Law had a younger brother, Humphrey, who was born in 1743 and died in 1817. But his wife was Elizabeth Freeland, not Agnes Hair. So who was this Humphrey Barbour named in the document? As he was a merchant who owned a bleachfield he was, presumably, another member of the linen Barbour family, but where did he fit in?

There is no mention of the births or a marriage between Humphrey Barbour and Agnes Hair in Kilbarchan Parish Records. Were they born and married in the years 1711 to 1740 when Kilbarchan Parish Records are missing? Further research has revealed an alternative primary source which verifies their existence. A four page pamphlet entitled ‘Answers for Agnes Hair relict of Humphry Barbour merchant in Kilbarchan, defender, to the petition of John Barbour merchant in Kilbarchan and William Blackwood in Oldyeard of Lochquinnoch, pursuers’ was written in 1752. A further connected reference to Humphrey and Agnes appears again in 1766 in Decisions of the Court of Session. In a dispute (Ann Murray v Elizabeth Drew 18.6.1766) concerning the legality of a bill of exchange, mention is made of a legal precedent in 1753 where Humphrey Barbour some days before his death delivered two bills to his wife, Agnes Hair. The Lords had found that these bills were properly conveyed to Agnes Hair and she won her case against John Barbour.

From this evidence it can be concluded that Humphrey Barbour (born and married between 1711 and 1740) was a younger brother of Baillie John Barbour and in 1752 after Humphrey’s death, Baillie John Barbour was disputing the right of his sister-in-law, Agnes Hair’s entitlement to the two bills Humphrey had delivered to his wife.

John Ramsay and later his heir James Ramsay are recorded in the Old Manse document as owners of both the Old Manse and adjacent properties and old bleachfields on the north east of the burn from the mid-1800s until the 1930s. The Ramsay family ran a very successful business as fleshers (butchers). What is now the dentist‘s surgery was their butcher’s shop and the manse garage, behind the premises of Kilbarchan Chiropody, (formerly the Bull Inn) was their slaughter house.

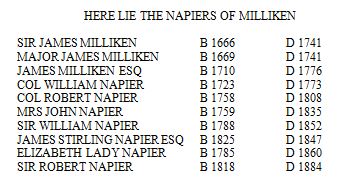

The document also reveals that John Ramsay was a shrewd businessman. When Milliken Estate was sold in the 1880s he purchased all or part of Over Johnstone Farm from the owners of Milliken Estate and in 1888 and 1889 sold off plots for building. By the 1891 Census Nos. 1-11 Easwaldbank and Reston Cottage in St Barchan’s Road had been erected on these plots and were occupied mainly by local weavers and tradesmen. The probable builders were Matthew Blair and John Gardner. They certainly were the builders of No 8 Easwaldbank. This plot was purchased by them jointly in 1889 and in 1891 the building housed a number of families including John Gardner and his family.

The document on the Old Manse is of some significance because it has given clear indication of lines of research into information on little-known residents in the village in the eighteenth century and the building of Easwaldbank. If anyone in Kilbarchan holds any old documents which might similarly add to the village history please contact Helen Calcluth or Russell Young, or e-mail The Advertizer.

© 2011, Helen Calcluth (Click on images to enlarge)

The first known building on the site appears on the 1857 Ordnance Survey map. The accompanying notes described it as a strong stone building supporting a large waterwheel which helped to pump water from the then-drained Barr Loch. It was built at the expense of Colonel McDowall, owner of the Castle Semple Estate from 1841, so it probably dated from the late 1840s.

The first known building on the site appears on the 1857 Ordnance Survey map. The accompanying notes described it as a strong stone building supporting a large waterwheel which helped to pump water from the then-drained Barr Loch. It was built at the expense of Colonel McDowall, owner of the Castle Semple Estate from 1841, so it probably dated from the late 1840s.