The final big drainage scheme was to drain Barr Loch, but keep Castle Semple Loch full of water. This scheme was the inspiration of another local landowner. In 1813, Adam of Barr purchased the whole of Barr Loch, plus about 100 acres of Castle Semple Loch. The first part of his plan was to dig a circular ditch, or canal, right round Barr Loch, ( see image above) to prevent the water from the burns pouring in, and carry their water into Castle Semple Loch.

The second plan was to carry the water away from Barr Loch to the Black Cart down a canal which would bypass Castle Semple Loch. Adam started the lower end of his drain at the Black Cart near Elliston Bridge, where the outfall can still be seen.

The second plan was to carry the water away from Barr Loch to the Black Cart down a canal which would bypass Castle Semple Loch. Adam started the lower end of his drain at the Black Cart near Elliston Bridge, where the outfall can still be seen.

The next 800 metres were in full view of Castle Semple House and had to be buried in a stone-lined tunnel. The tunnel then changed to the open canal which can still be seen following the south side of Castle Semple Loch. The canal connected to Barr Loch via a tunnel under the causeway which crossed the lochs. The scheme was carried out in 1814 by masons and Irish navvies. The water at the lowest point of Barr Loch, which was too low to drain away naturally, was raised from the loch bed up into the canal by a pump driven by a water wheel at Hole of Barr.

Although the works cost £10,000, the annual profit generated from oats and hay grown in the former loch bed, was about £1,500 a year, and the scheme paid for itself in a few years. Barr Loch had become ‘Barr Meadows’ and Adam’s scheme kept 170 acres of former loch bed dry and under crop for more than 131 years. One morning in 1946, locals were astonished to wake up and find that what had for generations been green meadows, was now a loch again. A lack of maintenance had led to the failure of the sluices and the turning of Barr Meadows back into Barr Loch.

In future, the lochs are likely to remain safe from the whims of wealthy landowners, thanks to the establishment of the nature reserve and country park. However, when visiting Castle Semple Loch, it is worth remembering that at various times in the past it was possible in a dry summer, to walk across the loch.

©2015, Stuart Nisbet, Renfrewshire Local History Forum ( Click image to enlarge )

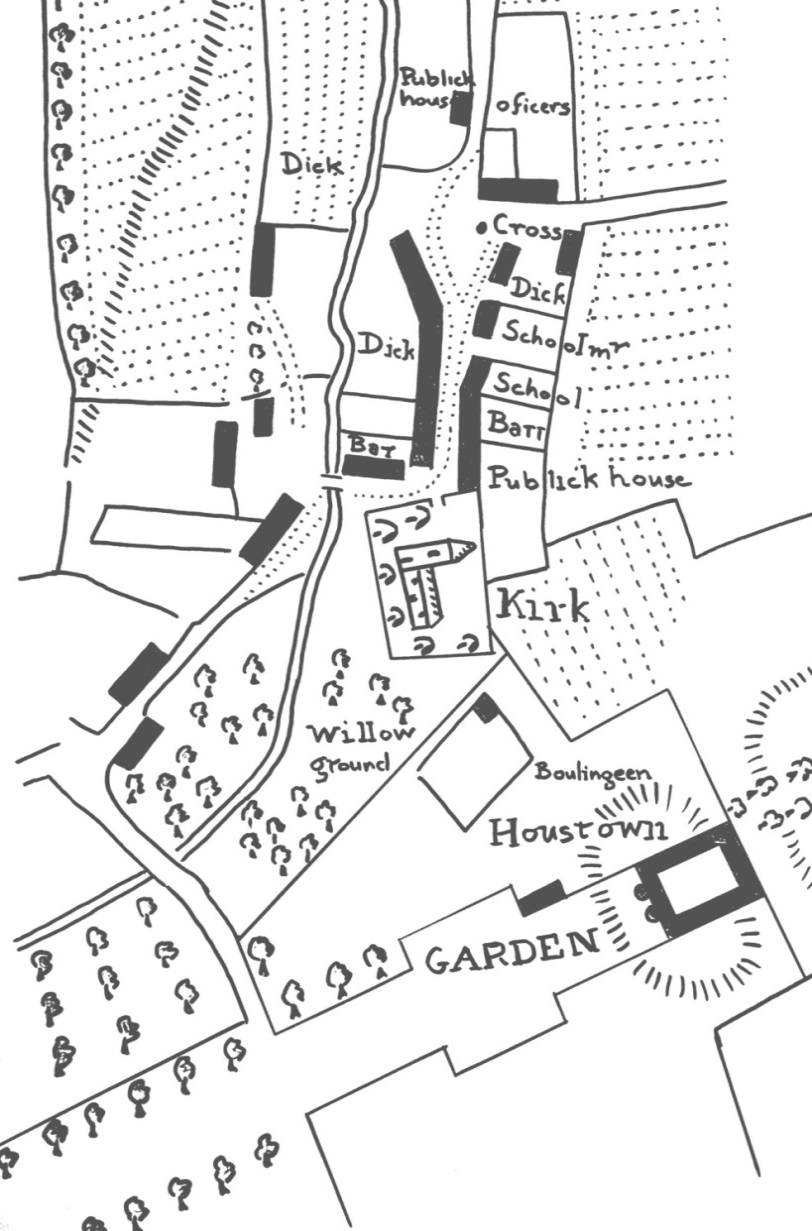

Due to the changes of owners and transformation of the estate around the time of the forming of the planned village, there was little evidence to confirm these descriptions. However the newly discovered estate plans, c.1780, show that the descriptions weren’t fantasy, but were in fact correct. They show a large square keep with a central courtyard, elevated on a mound. Even the turrets flanking the entrance can be seen on the plan.

Due to the changes of owners and transformation of the estate around the time of the forming of the planned village, there was little evidence to confirm these descriptions. However the newly discovered estate plans, c.1780, show that the descriptions weren’t fantasy, but were in fact correct. They show a large square keep with a central courtyard, elevated on a mound. Even the turrets flanking the entrance can be seen on the plan.