Waterfall formed by a breach in the old Elderslie Cotton Mill Dam. (see sbove)

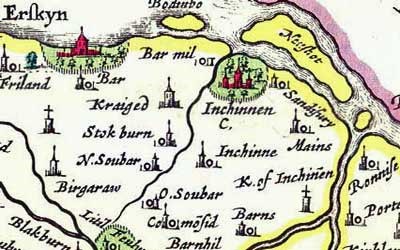

Renfrewshire had numerous cotton mills. The best-known mills were on the main rivers, the Black Cart, White Cart and Gryfe. However some lesser burns, including the Old Patrick Water at Elderslie, also powered large cotton mills from the 1790s.

The Old Patrick Water drops steeply from the waterlogged Caplaw Moss, down through Elderslie, and into the Black Cart between Johnstone and Linwood. Traditionally the burn powered meal mills at Elderslie Mill and Mackies Mill. The name Mackies Mill still survives as the name of a farm half way up the Old Patrick.

In the 1720s Houston of Johnstone got permission from Claude Alexander of Newton to built a dam near Craigmuir farm, just before the Old Patrick drops 60 metres over a succession of spectacular waterfalls. This dam diverted part of the burn’s flow for two miles, across to Johnstone. The purpose was to turn a “water engine” and pump water out of Houston’s Quarrelton coal field. In 1728 an apprentice was indentured by Houston of Johnstone to look after the “Water Wheel, Pumps and Gins, for out-taking his coal of Quarrelton and for draining the water therefrom”.

Elderslie meal mill was situated in Elderslie village, just above the Main Road. In 1791 the site was purchased by John Clark, a wright from Paisley, who built a much larger mill to spin cotton. In 1794 Clark also built Caplaw Dam, up near the source of the Old Patrick on Caplaw Moss, at the former Peesweep sanatorium. This dam was to store water for his new cotton mill. Caplaw Dam and its reservoir still survive up on the moors. Down in Elderslie, Clark also built another large dam to provide a 30 foot fall to power his cotton mill wheel.

Elderslie cotton mill was located on the Main Road, between the Old Patrick and the Wallace Monument. Soon after construction, John Clark sold the mill to the King brothers of Lonend in Paisley, who were partners with Robert Corse at Johnstone Old Cotton Mill. The two cotton mills were run for many years as one business. By 1823 Elderslie cotton mill had 9,400 mule spindles and the water wheel was complimented by a steam engine.

Elderslie cotton mill passed through various owners and, after the decline of the cotton industry, persisted as a clothing factory. The mill was typical of the tall whitewashed Renfrewshire cotton mills, and was finally demolished about 50 years ago. The nearby dam and sluice survive, although the dam is breached, forming a spectacular waterfall.

From 1793 further potential mill situations on the Old Patrick water were advertised in the press. This led gradually to further use of the Old Patrick water to supply power and process water to various other industries further upstream. The first was a large paper mill, built at Patrickbank in 1815 by Vallance and Lamb. This was driven by a 30 foot fall, and the manager’s house was at Leitchland nearby. By the 1820s the paper mill was worked by Walter Millar, with three vats for making paper. In the 1830s it was part of the Collins paper empire and the mill still had water rights to Caplaw reservoir.

By 1841 the paper mill became Partickbank print works. Much of the printworks still survived into the 1990s as part of the much larger Stoddart’s Carpet Factory which stretched further downstream. Both were razed and redeveloped with housing shortly after 2000. Only the dam and lade survive in the glen.

Slightly further upstream, at another spectacular water fall, Glenpatrick Distillery was established by the 1840s. This led to the Old Patrick being more commonly known as the Brandy Burn. Despite the demolition of all the mills, various traces of their dams and lades can still been seen when walking along the banks of the Old Patrick.

Stuart Nisbet © 2011