The book launch by Derek Alexander of ‘RENFREWSHIRE a Scottish County’s Hidden Past’ was held in Waterstone’s in Braehead on the 14th of June. Derek Alexander and the late Gordon McCrae, are co-authors of the book. In his address at the book launch Derek read some excerpts from the book and expressed his hope the book would encourage others to look for Renfrewshire’s ‘hidden past’.

Derek is the Head of Archaeological Services for the National Trust for Scotland and has been an active member of Renfrewshire Local History Forum for many years.

Derek is the Head of Archaeological Services for the National Trust for Scotland and has been an active member of Renfrewshire Local History Forum for many years.

Gordon was a noted local historian and studied archaeology at Liverpool University. Past students of Paisley University (the University of the West of Scotland) will remember him as its Depute Librarian.

Gordon was a founder member of Renfrewshire Local History Forum in 1988. His passion for local history and archaeology and unbounded enthusiasm is almost legendary. He organised and led numerous Forum field trips round the county, liberally sharing his extensive knowledge – and boiled sweets! His sudden death in 2005 was a tragic loss to the Forum. This book has been dedicated to his memory.

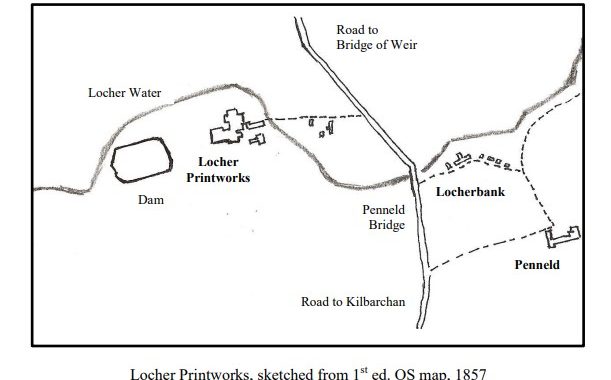

The book covers archaeological sites in Renfrewshire, East Renfrewshire and Inverclyde from the Palaeolithic to Early Modern Times. The archaeological sites are set within their historical context and the book is illustrated by more than one hundred maps, plans and illustrations.

Many local sites, in or near the villages where the Gryffe Advertizer is distributed, are covered in the book. These include, among others, Castle Semple Estate and the Collegiate Church at Lochwinnoch, Whitemoss and Barochan Roman forts near Bishopton, the excavation at South Mound in Houston, the late Bronze Age homestead at Knapps, Duchal Castle near Kilmacolm, the mote hill on Old Ranfurly Golf Course in Bridge of Weir, a moated manor and enclosure near the Wallace Monument in Elderslie, the crannogs in the Clyde at Langbank, Elliston Castle and the Midton Lime Kiln at Howwood, and excavations at the Old Churchyard and the Weaver’s Cottage in Kilbarchan.

For those interested in the seeking out archaeological evidence for the history of Renfrewshire, ‘RENFREWSHIRE A Scottish County’s Hidden Past’ is an excellent resource. For the many walkers who roam around our local area, the information in the book will provide additional points of interest in their walks. ‘RENFREWSHIRE A Scottish County’s Hidden Past’ (published by Birlinn Ltd.) can be obtained from Renfrewshire Local History Forum as well as from commercial booksellers.

© 2012 Helen Calcluth