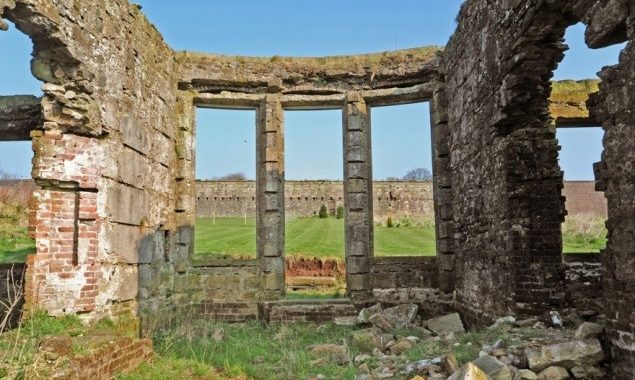

View of walled garden from ruined pavilion

The estate of Castle Semple in Renfrewshire was the seat of a leading Scottish landowner since the medieval period. The Semples were part of the Royal Court from the reign of Alexander II in the 13th century. By the 1580s Castle Semple included gardens, parks and woodland, evident on Timothy Pont’s survey.

The status of the estate is reflected in charters by King James IV to John Lord Semple in 1501, granting the lands, park, tower, and the fortalice of Lochwinnoch, and lands of Castleton. In 1504 John Lord Semple built a Collegiate Chapel amongst the gardens and orchards of Castle Semple, just behind the Castle of Semple. The precincts included ten roods (2.5 acres) of land directly adjacent, for priests’ dwelling houses, gardens and fruit trees.

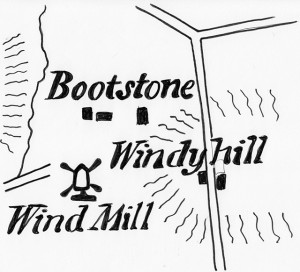

Castle Semple Collegiate Chapel survived the Reformation, and the priest’s gardens merged with Castle Semple’s garden. A detailed survey of 1733 shows a scatter of buildings and small enclosures directly south of the Chapel. Renfrewshire Local History Forum (RLHF) have carried out fieldwork on the site, including geophysics, which has identified several structures and at least one building, possibly a priest’s dwelling, near the Chapel and garden.

The fortunes of the Semples declined in the late 17th century. In 1726 Castle Semple was sold to Colonel William McDowall, a sugar planter recently returned from the Caribbean. At the same time, the Colonel purchased the Shawfield Mansion in Glasgow with its five acre garden, orchards and pavilions.

At Castle Semple, the Colonel demolished the old Castle of Semple, one of the largest towerhouses in the west of Scotland. On the same site he built one of the earliest Palladian country villas in Scotland. The mansion had a panoramic frontage, including four pavilions fronting Castle Semple Loch. Although the mansion was demolished to its basement in the 20th century, the four pavilions survive, each as private dwellings.

In the late 1720s, Colonel McDowall employed surveyor John Watt, uncle of James the engineer, to measure the old garden. He described the ‘old garden in which the chapel house stands’, enclosed by a wall and measuring 3 acres 2 roods.

He also brought garden expert William Bouchert to Castle Semple to lay out his new estate and policies. Bouchert carried out planting and improvements for many other leading estates, including Castle Kennedy, Auchincruive, Blair Castle, Duff House, and Rossdhu. From 1727 to 1730, Bouchert diverted the burn behind Castle Semple to feed water features, including fish ponds and cascades. Beside the ponds, an ice house and a grotto survive.

In front of the new mansion, facing the loch, an inner court was formed, enclosed on four sides by the house, the inner east and west pavilions, and a low wall to the front. A stone path crossed the inner court from the front door of the house to the wall, where three steps led up to an outer court, consisting of a flower garden and large oval lawn.

To the rear of the mansion, the Colonel retained the footprint of the Semple’s original garden and orchard, covering five acres. By 1780 the old garden was partly a bowling green. In the western half, closer to the Collegiate Church, were vineries, peach and citrus houses, a conservatory and a hot house. The hot house was described as the best in Scotland, equal to that of the Duke of Argyle.

(Click on image to enlarge)

From the 1780s, Castle Semple’s garden was transferred 500m north to a new location on a south-facing slope at the old settlement of Sheills. This developed gradually into the massive buttressed walled garden with brick and sandstone details. The walls still survive, although the garden’s pavilions and outbuildings have been unroofed for a century and are in a ruinous state

In 1835 the garden was described as being laid out with great beauty, with long ranges of conservatories, hot-houses with the choicest fruits, a pinery, extensive flower-garden, shrubberies of rare plants, a fish-pond surrounded by every variety of rock plants, and every requisite for horticultural purposes.

Castle Semple estate survives as a Country Park, relatively untouched by modern development. Its gardens and policies provide a unique opportunity to study the estate of leading landowners over 700 years and RLHF are continuing research and fieldwork on the estate.

© 2014 Stuart Nisbet, Renfrewshire Local History Forum