In 1712 an Act was passed restoring patronage to the Church of Scotland. This meant that the patron of a parish church, usually the local Laird, and not the congregation chose the minister. Because of various unpopular settlements of ministers, dissenters (also know as seceeders) from seventeen parishes in Renfrewshire set up their own church at Burntshields on the hills above Kilbarchan. The original congregation included 78 members from Kilbarchan, 47 from Paisley, 20 from Houston, 32 from Killochries in Kilmacolm, 51 from Lochwinnoch, 7 from Kilbirnie, 3 from Beith and 82 from Greenock and Inverkip.

This church called Burntshields Burgher Church was built in 1745 and opened the following year. The walls were built by the members of the congregation and the rafters were dragged up from the Clyde shore by horses. The church had seating for 600 and was referred to as the Big Sclate Hoose – so presumably had a slate roof, a novelty at the time among the thatched roofs of the ordinary houses. This was the first seceeders’ church to be built west of Glasgow.

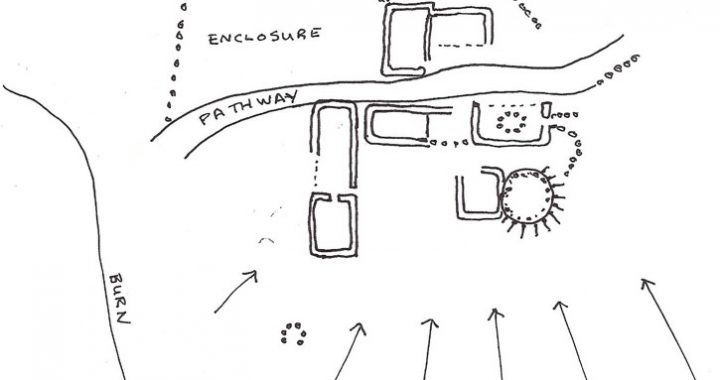

The church was situated in Minister’s Lane on the north of Burntshields Road, the road leading from Kilbarchan to Lochwinnoch. The manse was across the lane from the church. Burntshields Burgher Church ran its own school in a nearby barn. This school was still in existence as a country school long after the church closed in 1826.

Little evidence of the church remains today. A memorial obelisk to the church is now in the garden of nearby Burntshields Cottage and old gravestones are rather irreverently incorporated in the garden wall.

In 1790s there was some dissension in the church and the congregation split. In 1792 one group removed to Johnstone with the Rev.Lindsay. This was the origin of St Paul’s Church in Johnstone. Another group moved to Lochwinnoch to set up a new church there (later to become Calder Church). The third group remained at Burntshields.

In 1826 the Burntshields Church closed and the congregation moved from the country district and set up a new chapel, in Bridge of Weir, where there was much need of a church due to the rapid increase in the population after the establishment of cotton mills on the Gryffe. This chapel was to become Freeland Church, in Bridge of Weir.

Two square rather ornate communion tokens from Burntshields Church, both dated 1793, are in the collections of Paisley Museum. One token is in almost mint condition. In 1971 the Burntshields communion service, which was discovered in an old basket in a loft where it had lain forgotten for years, was given to Freeland Church in Bridge of Weir . The inscription round each flagons reads ‘GIFTED TO THE ASSOCIATE CONGREGATION OF BRWNTSHIELDS AWGUST 1769’ and the inscription on each cup reads ‘BELONGING TO THE ASSOCIATE SESSION OF BURNTSHIELDS 1774’.

© 2010, Helen Calcluth