By Bill Speirs of Johnstone History Society

The Old Peesweep Inn

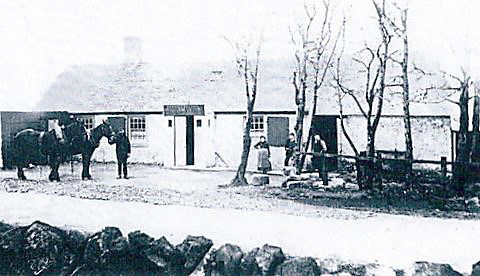

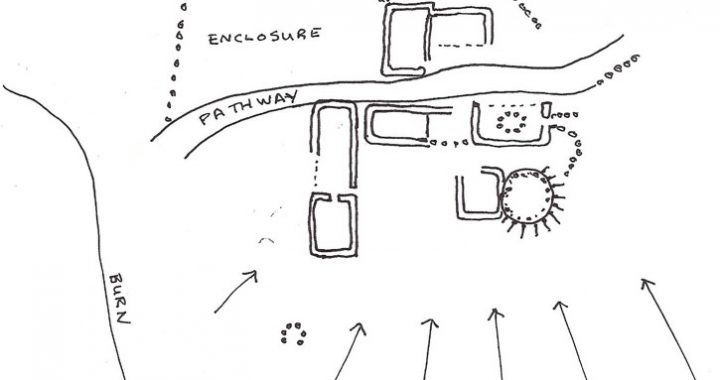

The Peeesweep Inn sat on the Gleniffer Road at the northeast corner of the crossroads east of Lapwing Lodge. All that remains to indicate the site is the raised patch of ground where the inn and its garden once stood. The inn was built between 1810 and 1840 when one traveller described it as “an old fashioned and bien howff where a farle of oatcake and a gill of mountain dew could be had”. It was still occupied as a private residence in 1931.

In 1856 the inn was documented as a lowly one storeyed building with a kailyard behind and a rowan tree at the front, perhaps to keep witches and evil spirits away in this isolated spot. The proprietor of the Peesweep Inn in the 1850s was David Stevenson, with his wife Barbara, their daughter Janet, and sons David and Thomas.

Before the death of their father in 1866, the two brothers had moved to Johnstone where both became successful business men. Thomas had various commercial interests in the town with his main commercial and residential premises at 74 High Street. He served on the Johnstone Town Council for 10 years, and was Provost, a position he held with considerable distinction, for several years from 1882.

Soon after David Stevenson, sen., died his son-in-law, William Muir, who had married David’s daughter Janet in 1864, took over the proprietorship of the Peesweep Inn. William Muir as landlord at the Inn, however, fell foul of Her Majesty`s Constabulary who had been making frequent complaints on account of “Sunday trafficking” (a lock-in in modern parlance) despite repeated warnings to desist. Eventually, in April 1889 the Peesweep Inn was unanimously refused a licence. The Justices had had enough. There would be no more beers, wines or spirits sold there ever again. William Muir left the inn before 1891 and moved to the Bent, a neighbouring farm, with his wife and family. The inn was subsequently occupied by John Pollock, a roadman, and in 1901 by Robert Woodrow, a railway surface man and their families.

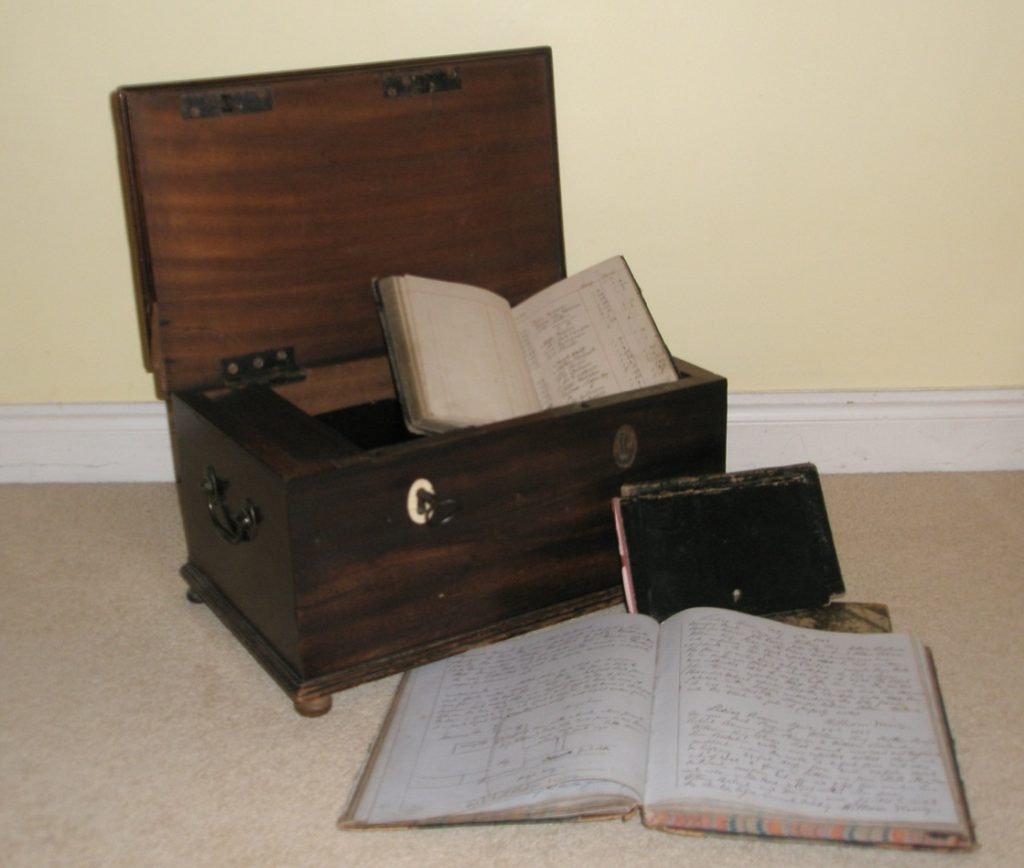

Perhaps the most important guests who frequented the Peesweep Inn were a number of notable gentlemen from Johnstone, Paisley and Glasgow who called themselves the Peesweep Club. The Peesweep Club was formed in 1849 and the members met during April or May each year at the inn. They took part in various sports, some aquatic when there was sufficient water in the nearby Hartfield Loch (also known as the Peesweep Dam). After the initial round of sports the members would adjourn to the hostelry for dinner which would include the sma’ still whisky “that streams in the starlight when kings dinna’ ken”. The meeting would finish with a group photograph of the members, occasionally gathered posing round a wagon in the yard. Baillie Thomas Stevenson of Johnstone, who had been brought up at the inn, was one of the members and would surely have got a warm welcome from his sister, Mrs Muir, the landlady.

Despite its loss of licence the Peesweep Inn probably continued to be a meeting place for the next thirty years. The Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire Hunt met at there on a dismal day in 1893 when the “rain fell copiously” and the surroundings were “bleak and barren-like”. In 1912 bannocks and Dunlop cheese, home baked scones, fresh butter, eggs, and milk were all available at the inn which was then a favourite destination on evening rambles for various walking clubs, such as the Pickled Ingan Club, the Peep o’ Day Club and the Kail Stock Club, but alas no Peesweep Club.

©2013 Bill Speirs