For over a century, five generations of the Finlayson family owned the flax mills in Johnstone. William Finlayson, born in Dunfermline in 1786, had a successful manufacturing business in Glasgow and was one of the first in Scotland to spin flax on machinery. In 1844, seeing Johnstone as an expanding new town, William, in partnership with his sons, James (1823-1903) and Charles (1825-1874), set up a flax spinning factory in the town.

In 1848 William’s sons, James and Charles, in partnership with a young Englishman, Charles Bousfield, founded Finlayson Bousfield & Co. and took over Barbush Cotton Mill, situated on the south bank of the Black Cart at Johnstone Bridge on the High Street as their new flax spinning mill. In the mid-1850s the company also owned Lilybank Mill, a smaller mill, situated on land behind Lilybank House in Brewery Street.

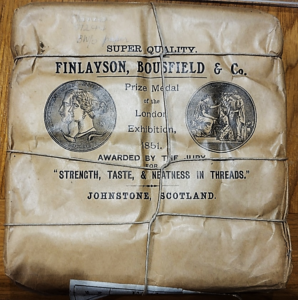

The company processed raw flax before it was spun in the spinning mill and the final process was the finishing and dyeing. In the early days, Finlayson Bousfield & Co. produced quality white and coloured threads. They sent their quality goods for display at national and international exhibitions. Probably their earliest exhibition was the London Exhibition in 1851 where the company was awarded a prize medal for the “strength, taste and neatness in threads”. To celebrate the award and to promote sales, Finlayson Bousfield used wrapping paper for their packages showing images of their 1851 prize medal. Two fine examples of this packaging are on display in Johnstone Museum

The company quickly prospered and expanded and by 1856 Finlayson Bousfield’s Barbush Flax Mill was described as “an extensive establishment, adjoining Johnstone Bridge, for the manufacture of spinning thread”. By the 1860s Finlayson Bousfield & Co. had become the largest industrial plant in Johnstone and had its head office at 11 St. Enoch Square in Glasgow.

By the 1870s James’s sons, William, Archibald and James, Jun., were employed in the mills and business continued to develop and expand. The firm now owned Lancefield Mill, a small mill in Clark Street, and, in 1873, built a second large flax mill on the North bank of the River Cart at Johnstone Bridge. In 1881 Finlayson Bousfield’s Johnstone flax mills were documented as having a capital of £187,003 and 1700 employees, and were regarded as the largest flax mill in Scotland.

James and Charles had become not only successful wealthy businessmen, but also men of importance and influence in Johnstone who played a significant part in the development of the town. James had played a key role in the creation of Johnstone as a burgh in 1857. He founded the Flax Mill Workers Co-operative Society in 1866 which served the town for almost a century and built workers’ houses in Clark Street in 1872. In his sixties James stood for parliament and served as MP for Eastwood in 1885-1866. Charles, before his death in 1874, organized the building of Lilybank Bowling Green, for the use of the company’s employees. It has stood the test of time and is still a popular bowling green in Johnstone today.

For some years the company had been exporting abroad, notably to USA and Australia, where, Richard Allen & Co. of Melbourne were sole agents for Finlayson Bousfield of Johnstone. In 1878 James’s son, Archibald, was sent to USA to explore the possibility of setting up a new mill. Finlayson’s Flax Spinning Mill in North Grafton, Massachusetts, was up and running before 1885.

After consultation in 1897 with other well-established flax mills in Renfrewshire, Ireland and USA, Finlayson Bousfield & Co. in Johnstone and Finlayson’s Flax Spinning Mill in North Grafton, USA were founder members of The Linen Thread Company (1898-1968).

Packaging: Courtesy of Johnstone Museum

© 2022 Helen Calcluth. Renfrewshire Local History Forum