The best-known and most valuable mineral which was worked in Central Scotland was coal. Beyond coal, the mineral ghost of Renfrewshire was limestone. Lime had always been used in building, for mortar, harling (roughcast) and plaster. However, from the eighteenth century, much larger amounts of lime were sought for improvements to farmland. By adding burnt and powdered lime to the soil, crop yield could be greatly increased. Limestone was particularly important in regions with heavy clay soils, such as Renfrewshire. The lime was added liberally to both arable and pastoral land, at the rate of up to thirty carts per acre.

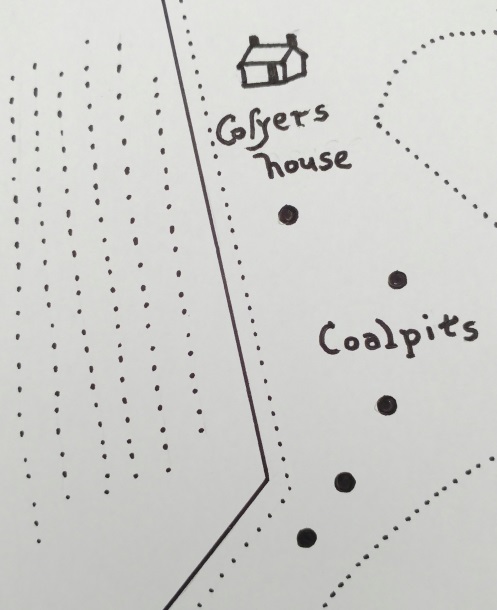

Limestone is found in thicker seams than coal, and was usually quarried from the surface. Thus traces of former workings are more abundant than with deeper coal mines. Unlike the white chalky lime found in the south of England, Renfrewshire lime is a hard, brittle, dark grey rock. It was formed under shallow seas in the Carboniferous period and often contains shells and crinoids (stems of sea lilies). Lime quarries were highly valued by fossil collectors who raided them for fish and reptile remains. Before good roads were built, the coal to fuel the lime kilns had to be found locally. Despite the relatively thin and indifferent quality of the coal in the Gryfe area, it was ideal for lime burning. In many cases it was expressly stated that the coal was only to be worked for lime burning.

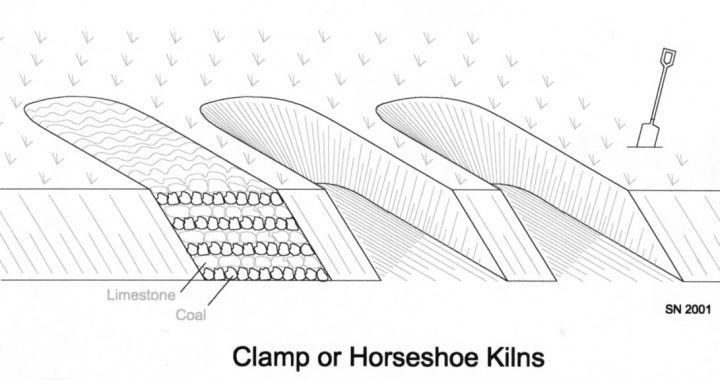

In the 1790s, Kilbarchan parish had seven coal mines, all but one owned by the Milliken family. At each of these mines, the main use of the coal was to fuel lime kilns. The most familiar lime kilns were large stone-built draw kilns. Less well known, but just as common, were clamp kilns. These were long hollows dug into a slope in which the limestone was repeatedly burnt. Until recently, virtually no lime working sites were officially recorded in Renfrewshire. New fieldwork has now identified more than a hundred. Hints of early working come from place names such as Lime Craig Park (Johnstone), Kilnknowie (Corseford), and Limekilns Plantation (Lochwinnoch).

© 2017 Stuart Nisbet, Renfrewshire Local History Forum