The name Houston is one of the oldest family surnames in Kilbarchan dating back to the early 1600s. John Houston, the Kilbarchan linen merchant, married Margaret Naismith from Lochwinnoch Parish in 1750 and had nine children. He was a leaseholder in the village with houses and a yard in Merchant Close, and in his later years lived in Old Hall in Shuttle Street.

John Houston’s linen manufactury in Kilbarchan was established in or before 1755 when he bought the land adjacent to the Barbours’ Auchinames Bleachfield. By 1779 some of his weavers were working in silk, producing quality silk gauze for export to Dublin. He was extolled as one of the principal manufacturers in the village and a ‘Dublin Merchant’ by Semple in 1782.

Like other of the Kilbarchan merchants, John Houston had business interests outwith the textile trade. He owned a large brewery in Kilbarchan. When the linen industry in Kilbarchan was in decline in the 1780s, John Houston must have felt the need to increase his income or consolidate his capital. In 1786 he placed an advert in the Glasgow Mercury – ‘To be let at Kilbarchan – a brewery and malthouse with every article necessary for carrying on the business, in good condition’ and a ‘large new still to be sold’. It is not known if a subsequent letting arrangement, or the sale of the still, took place.

Rather than concentrate on his Irish interests, John Houston entered into partnership with a Paisley manufacturer in 1789. This newly established Paisley firm, Dundas Smith & Co., specialised in plain and embroidered muslins. The business had a factory in Paisley and employed weavers, warpers, winders, tambourers (embroiderers) and clippers. From 1790 and until 1802 Dundas Smith & Co. marketed their goods in England and exported cotton and linen goods to Jamaica. John Houston lived to a ripe old age. In 1807 he was described as ‘about 87; quite agile and strong; can walk to Paisley and return as cleverly as a man of twenty’.

© 2022 Helen Calcluth

Further information on the Speirs, Barbours, Hows and Houstons is contained in “Kilbarchan and the Handloom Weavers” (Chapter 3, pp 31-42). Available on the website Publications.

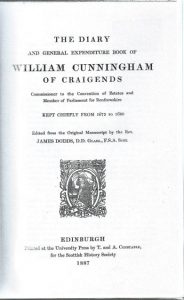

Over one hundred years before John Cuninghame, 13th Laird of Craigends kept a diary, William the 8th Laird, too, kept a diary. Unlike the 13th Laird’s very personal diary, William Cuninghame’s diary was mainly in the form of an account book of his household expenses, but it still gives an interesting insight into his life and activities.

Over one hundred years before John Cuninghame, 13th Laird of Craigends kept a diary, William the 8th Laird, too, kept a diary. Unlike the 13th Laird’s very personal diary, William Cuninghame’s diary was mainly in the form of an account book of his household expenses, but it still gives an interesting insight into his life and activities.