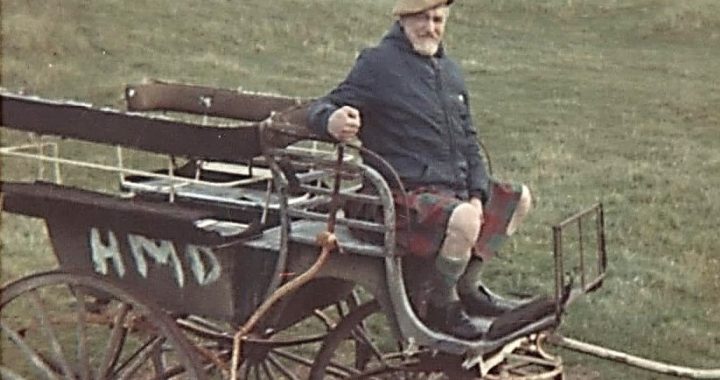

In Callander, Ralston is well remembered as one of the real characters in the town. He always wore a kilt, except for riding jodhpurs – and they were tartan as well. On some occasions he added a pheasant’s feather on his cap. He is known to have spent to have spent a holiday on Coll with friends from Callander in 1969 and, even on holiday, he dressed in his usual attire of kilt and cap

The Gudgeon home in the 1960s appears to have been a menagerie containing a diverse collection of animals and birds – numerous spaniels including Clooney, the big springer spaniel, and Tramp, the Labrador; umpteen cats; Ruadh, the fox; a hamster which ran around the house when “Gudge” and Mrs Gudgeon played the piano; and hawks, but the hawks were kept outside. One night Ralston brought his fox into the Shaftsbury Inn, and the landlord remarked that it was better behaved than many dogs.

The Gudgeon children’s friends in Callander were fascinated by Ralston. They would follow him along the street calling out the old rhyme, “Kilty Kilty Cald Bum”. To the delight of the children Ralston would turn round and roar at them. They all took it all in good part. On another occasion, Ralston was sitting with a group of children at the putting green telling them of his time in North Africa during the war and his friendship with an Arab sheik. The children were fascinated, but a bit sceptical about the story. Just then a large car stopped in front of them and Ralston’s Arab friend (whom he had been expecting to arrive) stepped out to greet him. The children were speechless! As well as being sociable, talented and a bit of a romantic, Ralston seems also to have had a mischievous sense of fun and humour.

This mischievous sense of fun was not confined to teasing children. He was not averse to playing tricks on his friends and neighbours. One lady recollects from her childhood that her father, Mr Macrae of Beinn Dorain in Main Street, was concerned that his stairway ceiling was so low that tall people banged their heads on the way up. He asked Ralston to paint a wee duck to place on the stairs to remind tall visitors to “duck”. Ralston obliged – but gave him a real duck’s head! In hindsight the lady thinks it might have been stuffed. (Ralston’s son, Lin’s hobby was taxidermy.)

Ralston was still full of fun in his late sixties. As a regular a customer in the Mairie Stuart Bar in Glasgow’s MacDonald Hotel, he persuaded the barmaid, Yvonne Falsay, to dress in the Royal Stuart tartan to match the name of the bar. An image of Ralston toasting Yvonne, dressed as Mary Queen of Scots, appeared in the Evening Times on 23rd August, 1978.

He is still fondly remembered by older residents in Callander as “a big handsome Scotsman” ; “a real one off and a true gentleman”; and “a fabulous neighbour”. Ralston died in Thornliebank in 1984. His wife, Jessie, lived to the age of ninety and died in a nursing home in Lundon Links on 13th November, 1999.

Do any Habbies have any memorabilia or old family stories of the artist’s life when he lived in Kilbarchan in the 1920s or 1930s?

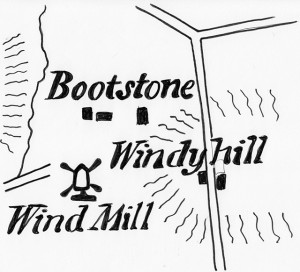

Click to enlarge.

© 2023, Helen Calcluth, Renfrewshire Local History Forum