The McDowalls of Castle Semple and Millikens returned from the Caribbean in the 1720s and showed the vast income possible from sugar plantations. Thanks to their experience, they became ‘fixers’ among Renfrewshire’s main landed families, arranging positions for sons as overseers, and marrying daughters to sugar planters.

The Maxwells of Nether Pollok (now Glasgow’s Pollok Country Park) were one of the biggest landowning families in Renfrewshire. They are not often linked to mercantile pursuits, but have a long slave owning heritage.

Pollok House

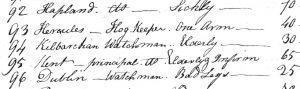

The connection started with Robert Colhoun, grandson of one of Glasgow’s original merchants or ‘Sea Adventurers’ who was a St Kitts planter in the 1660s. Robert sailed to St Kitts in 1724 as the McDowall’s slave overseer. By the 1750s he owned two sugar plantations next to the McDowalls. A training position was arranged on Robert’s plantation for James Maxwell, a younger son of Nether Pollok. In 1762, due to the death of the heir, James suddenly became Sir James Maxwell the new heir to Nether Pollok. While on St. Kitts, Sir James had courted Robert’s daughter, Fanny. Sir James came home and married Fanny Colhoun, the daughter of McDowall’s slave overseer. Large sums poured into Nether Pollok from Fanny’s dowry from her late father’s sugar plantations on St. Kitts, and the Dutch sugar island of St. Croix.

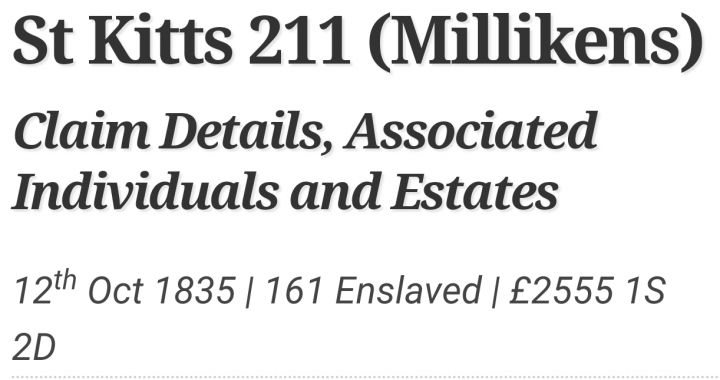

The family’s slave-owning heritage continued. In 1815, Elizabeth, the granddaughter of Sir James and Fanny Colhoun married Archibald Stirling. Thanks to the family’s Jamaica sugar plantations, where Stirling had spent most of his life, he was reputedly the richest commoner in Scotland. At the abolition of slave ownership in 1834, Stirling was awarded £12,517 for the loss of 690 enslaved Africans on his plantations. When the Maxwell male line died out, Archibald and Elizabeth’s son, William, became heir to Nether Pollok. Despite the slaving heritage of the Stirlings, the family adopted the double-barrelled ‘Stirling-Maxwell’ surname, to save losing the ‘Maxwell’ title.

Sir William Stirling-Maxwell purchased much of the art which now graces Pollok House. Their grandson, Sir John Stirling Maxwell, founded the National Trust for Scotland at Pollok in 1931. The Stirl.ing-Maxwells were one of Renfrewshire’s biggest landowners. Like many of Renfrewshire’s landed elite, they were also slave owners. Each acre of land in the family’s ownership was improved through the labour of one of their enslaved Africans.

© 2019 Stuart Nisbet